'Case Conference': the 1950s British journal

Richard Titmuss and a new 1950s social work

A context of a new British social work journal in the 1950s

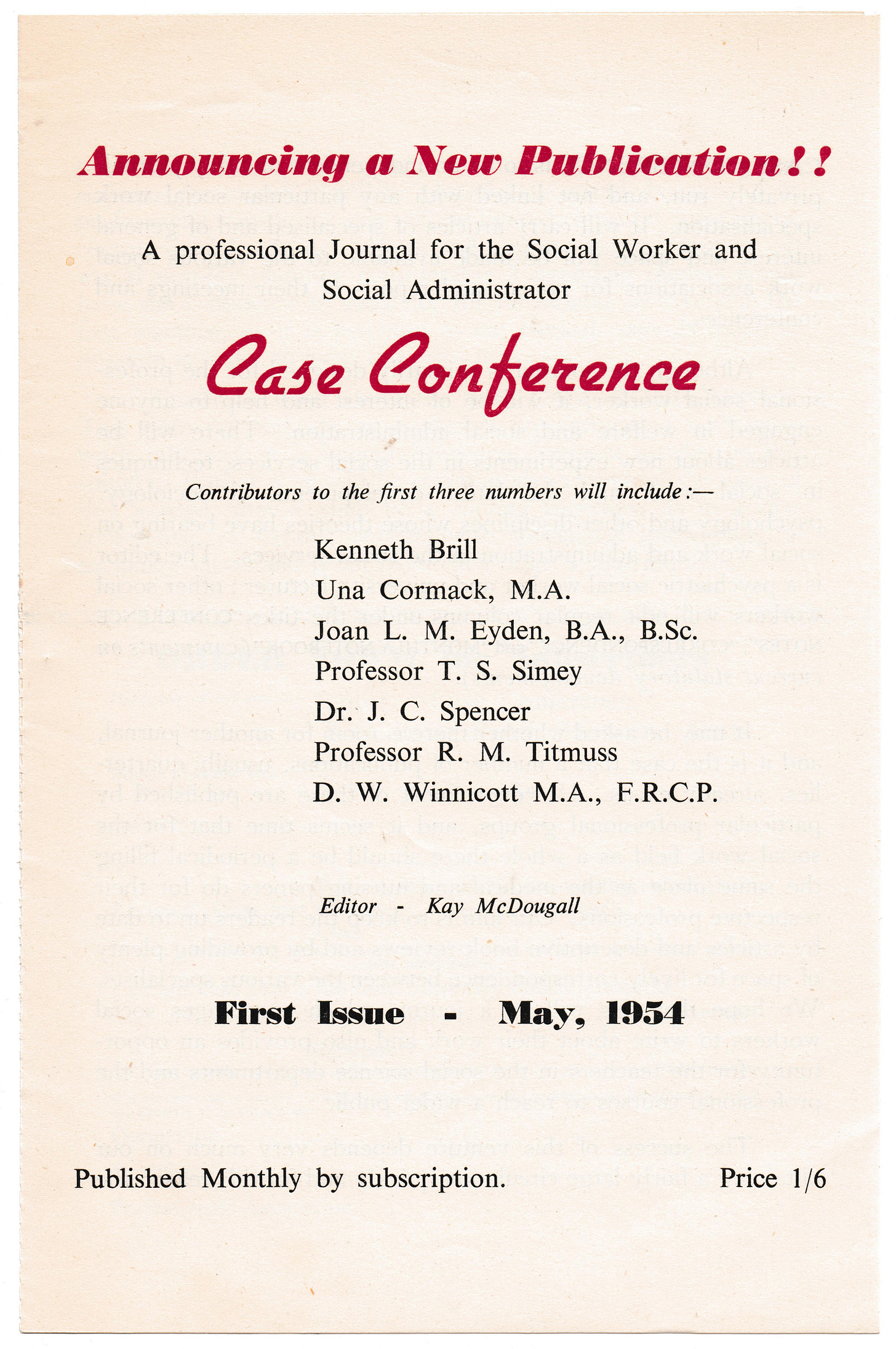

In early 1954, a leaflet began to circulate advertising a new British monthly social work journal: Case Conference; you see it at the top of this post. It was to be published more or less monthly (in latter years, the editor and printers took a summer holiday) from May 1954 until its anniversary number, Volume 16, Number 12, in April 1970, fifteen years. It had the same editor (Kay McDougall) throughout, because she owned it, and probably the same printer, because its printing company was managed by her husband (McDougall, 1970). Practical advantages, you might think, for starting a professional publication to have the money and a marital back-up. During that time, the journal’s office was visited by a Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, his photograph appearing in the last edition as part of the Editor’s signing off piece (below).

Looking at social work journals tells you something of the professional pre-occupations of the period, in the same way as looking at textbooks tells you what was important for the education of social workers. From time to time, I will return in these posts to the changing times reflected in the pages of various journals.

In this post, I look at the first edition of Case Conference. When I first came to it as a social work student in the mid-1960s, it was a chunky read, and also contained and was substantially financed by quite a lot of job adverts. But the first edition contains four social work job adverts from organisations that might well be personally known to the editor and just three major articles:

Titmuss, R. (1954). The administrative setting of social services: some historical reflections. Case Conference. 1(1): 5-11.

Brill, K. (1954). Case conference or jamboree: a year’s social work in a children’s reception home. Case Conference. 1(1): 12-17.

Eyden, J. L. M. & Cormack, U. (1954). Registration – the next step? Case Conference. 1(1): 20-5

The times were significant: it was nine years on from the end of the second world war, and things were getting back to normal, although as a London child I knew that there were still many bombsites scattered across the city, one of them my grandparents’ home where my mother lived while my father was away in India for the war. So we were living in two rooms in the home of one of my mother’s aunts.

Wartime rationing of meat ended more or less at the same time as Case Conference was first published; have a look at what school children are taught nowadays about rationing in this Internet information publication from the University of Oxford. And it was six years on from the implementation of the welfare state reforms in 1948, which got rid of the Poor Law and set up a new system of local government welfare services. Things were just getting going in social work, too, therefore.

The journal’s first authors

These are significant authors, too. Titmuss was the first professor of ‘social administration’ at the London School of Economics and Political Science (the LSE), fairly newly appointed (1950). He was largely self-educated, and had published the official history of social policy during the second world war (Titmuss, 1950). He virtually created the academic field of social policy in the UK, eventually leading it to become separated from the social work. Titmuss became a pre-eminent figure and led the most high-profile academic department in social policy studies until his death in 1973. See a brief biography of him given in a memorial lecture by Howard Glennerster in 2014.

Brill was a psychiatric social worker, who was one of the first children’s officers, responsible from the outset for one of the local government departments providing children’s services which formed the backbone of the development of social work in the ‘50s and ‘60s. He became the first general secretary of the British Association of Social Workers (BASW), the first unified membership organisation of social workers in 1970 and retired as a director of social services.

And Eyden, then and for many years a leading social policy academic in Nottingham, and Cormack, a long-standing active social work professional, were at the time of their article’s publication chair and vice-chair of one BASW’s forerunners, the Association of Social Workers. This organisation had been formed from the ashes of the attempt to create a federation of social work professional bodies in the 1940s.

These people were the glitterati of the newly-developing profession in the UK.

Titmuss on social work and its administrative setting

Titmuss (1970: 500) later described his 1954 article as ‘an argument for Seebohm in the interests of people and not in the interests of professional imperialism’. That is, he argued for the integration of specialised social services; ‘Seebohm’ refers to the chair of the government committee that recommended that, which was implemented in 1971, just before Titmuss’s death.

In his article, Titmuss’s ‘historical reflections’ refer to public recognition of social work ‘which would have seemed unthinkable in 1938 (p. 5)’, but notes uncertainty about its role, its ends and means and future direction in 1954. He interprets that uncertainty, unease, as reflecting a vitality to further establish social work’s position. It is that same vitality that we see in many countries in which social work and social development is gaining importance and establishing its role across the world today.

A series of official reports had looked at different fields of social work separately, studying social workers in isolation from cognate provision and their practice only as reflecting a personal relationship between client and worker. This hardens artificial distinctions and obscures common foundations in social work. It also failed to ‘examine the changing patterns of social needs and response (p. 6)’.

Two significant changes of this kind are:

The rejection of Poor law practice and philosophy;

‘Sudden and greatly increased demand by society for the services of the social worker (p. 7)’.

This reflected a greater interest in understanding people’s motivation and behaviour, not treating people in need of help as a mass. In turn, specialisation of function grew up centred on individual needs, but this neglects to see people as members of families. The pattern of social work development, therefore, was moulded by patterns of administrative structure, established as the price of other desirable things: developing local government, specialisation in medicine and wider social services (such as welfare benefits). Thus, how social work in the UK was organised was dominated by short-term administrative considerations. Some of the weaknesses of social work arise from problems of communication and mutual understanding created by these administrative issues; both administrators and social workers need to work together more.

Two reasons for the inadequacy of coordination are the need for prevention of human difficulties arising and using ‘our greater awareness of the psychological and social sources of need (p. 8)’. Responding to both of these issues requires two things:

continuity of care;

thinking through an individual’s needs as part of a family.

Whatever the setting, social workers trying to apply casework principles need to be able to do so without minimising administrative barriers. The Poor Law having disappeared, they see the needs as aspects of social relations, not as questions of eligibility.

That concern for the social is more significant at the local level than in departments of central government. Local government and its councillors and officials therefore have opportunities for pioneering new approaches. You can’t deal with these problems by looking only at social work education and skills, because being able to use education and skills relies on an appropriate administrative setting.

Referring to a report on social work education in the USA (Hollis & Tayor, 1951), he suggests that there was evidence there of too much concentration on ‘technique’. This encourages social workers to focus on ‘ “protected settings” suited to case-work’ (p. 9), rather than being concerned with the resources and structures that enable them to carry out their broad functions. This raises three issues:

The need to define the nature of social work specialisation, distinguishing between skills, functions and settings;

To do this, we need to look at the field as a whole, not at historical administrative boundaries;

To devise and use a more inclusive concept of social work, in which case-work and the effectiveness of services and settings in which in may be practised cannot be divorced (p. 10).

Practitioners, administrators and social scientists must cooperate in carrying out this analysis. Titmuss says:

The central principle of case-work – self-determination – and the twentieth century concept of prevention are indivisible. The first is a personal involvement; the second (in the world of today) is a social involvement (p.10).

The complex interactions required for casework to meet a need for help through relationships, can only be carried out in the insecurities and uncertainties of the highly-organised, complicated and self-conscious society of today; they are inseparable.

The Poor Law history is of a ‘from-above-downwards’ relationship. Societies ask for the social worker because of her skills, perception and ability to build bridges rather than thrust herself on society. Values have changed and so have the ends and means of social work.

Titmuss argues for social work values

Celebrating the erasure of the Poor Law, Titmuss is showing here how the interpersonal social work of the 1950s has the possibility of a more open responsiveness to ‘the social’. His argument also presages the concern that the social service structures within which social work operates must facilitate practice that develops ties across social barriers. He makes the connection to that stream of American thinking that focuses on the social highlighted in the work of the Abbotts and Jane Addams in Chicago and the settlement movement. He points to how that differs from approaches typical of the work of Mary E. Richmond, whose Social diagnosis is currently being considered in my history of social work in 20 books posts.

In the next post, I shall look at other contributions in the first issue of Case Conference and a later post will look at the information and issues that other contributors made to the journal in its first year in the mid-1950s.

Hollis, E. V., & Taylor, A. L. (1951). Social work education in the United States: The report of a study made for the National Council on Social Work Education. New York: Columbia University Press.

McDougall, K. (1970). Looking back. Case Conference, 16(12): 509-16.

Titmuss, R.M. (1950). Problems of social policy. London: HMSO.

Titmuss, R. M. (1970). (untitled). Case Conference. 16(12): 500-1.