The Pudding Lady’s cases

...and the politics of women's roles in early social work

This second post on ‘The Pudding Lady’ draws on the 1910 and 1916 publications about Miss Florence Petty in a ‘social work’ experiment in St Pancras in central London. In this post, I look at her analysis of some of her early cases, some of the commentary from her sponsors and then say something about a view of social work in the Edwardian period, prior to the First World War, revealed by this project. And return briefly to Mary (Mrs Humphrey) Ward, one of the people promoting this work.

Miss Petty’s cases

The book contains fairly factual accounts of 21 of Miss Petty’s early cases. More important is the summary (pp. 26-33) of them. It’s not clear how much she wrote this, or somebody else wrote the summary based on her case papers. The aim was to show family life in working class households in a poor part of London in this period (1908-10). It seems to be designed to show critics of working-class family standards how working class women were trying to bring up children well, despite their poverty.

St Pancras, the area covered, still contains the two of London’s major railway termini, next to one another. King’s Cross Station served, and still serves, the north-east of the UK, including Scotland. Post the second world war, in the 1959s and ‘60s, it was a major red-light district, a social role displaced in its new social status.

St Pancras itself is now the UK’s only international railway station, Britain being an island. You catch trains there that travel through a tunnel to European destinations. The undercroft of the station, in Miss Petty’s day a major cargo hub, now sparkles with glossy shops and eateries.

Nearby, there is a national science research hub and the British Library, built on land derelict for decades after Second World War bombing and ‘slum’ demolition. Up the hill between the stations, now a location for major corporate offices (Google and Microsoft have their UK headquarters there), you cross a major canal to ‘Coal drop yards’ now with more luxury eateries, a cultural university hub and the headquarters of the Guardian newspaper.

In the pudding lady’s day, its name discloses that this was the place where coal was delivered by canal and rail and stored. This fuelled Britain’s industrial revolution and heating and lighting for the metropolis. There was always employment here, and much working class housing.

The overall impression of the case studies is:

… exceedingly hopeful. “ The Pudding Lady “ was welcomed everywhere, by none more warmly than by the children who gave her that name. A renewed interest is surely the first thing. The woman who was so excited over her first pudding that she kept looking in the pot to see if it was really boiling, and Mrs. A., who sent her first raisin pudding round to the Welcome [centre of mothers and babies] on a plate, in order to receive our congratulations on it, are surely triumphant demonstrations of what tact and patience and enthusiasm can achieve. And could anyone want a higher compliment than Mrs. L.’s husband’s remark: “It’s usually cannon balls, but them’s real dumplings.” (pp. 26-7)

The apparent newness of it all led Miss Petty to go into the question of what the people ate before she taught them to make stews and puddings. A good many…already made stews, but dull ones. And Mrs. E.’s budget, reproduced in her own words, is a marvel of management (p. 27).

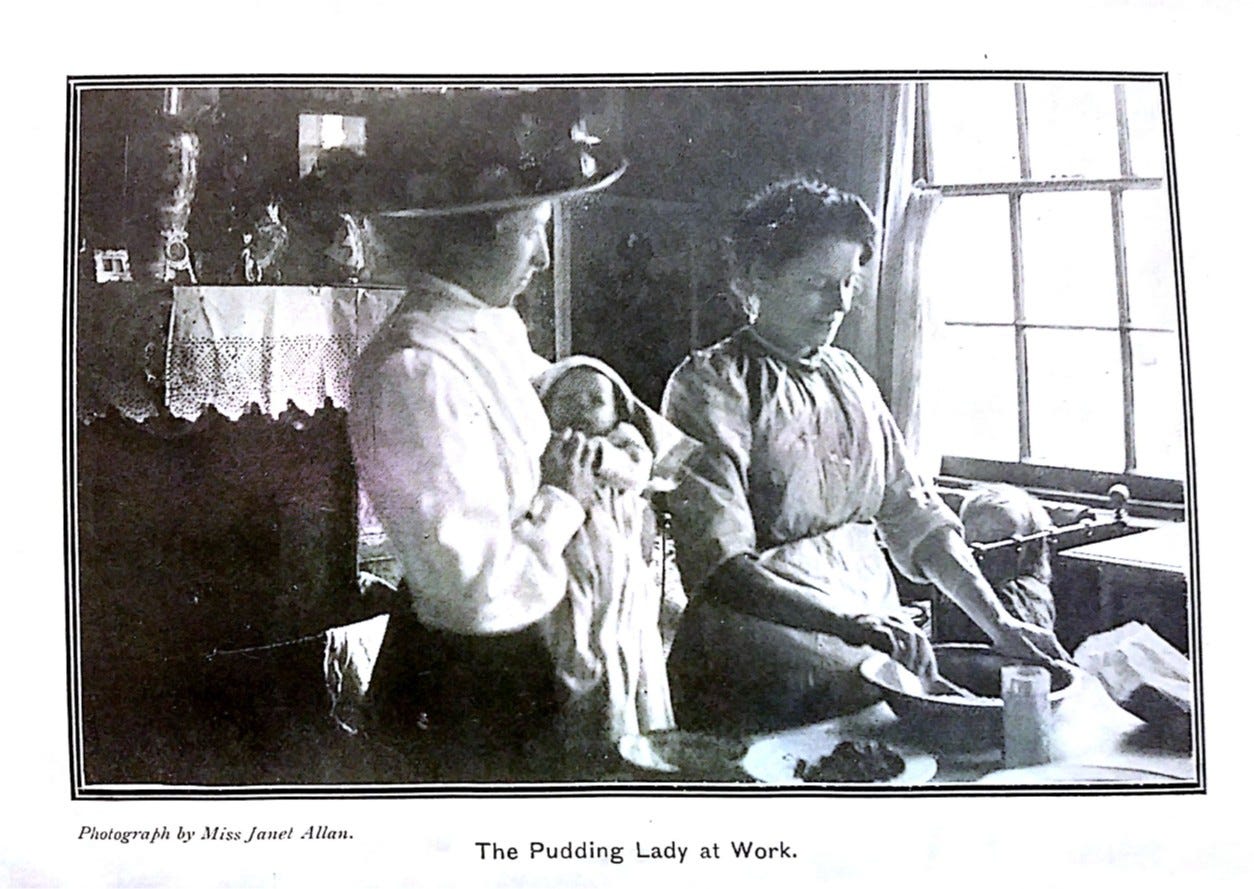

Cooking in one room or small apartments was difficult. Miss Petty describes her pleasure in ‘holding the baby’ while the mother cooks, and forms one of the striking pictures in the book’s first edition.

Examples of what women had to cope with are:

…the case of Mrs. Q., where the pudding had to be mixed on a chair, or the case of Mrs. L., where two babies wanted minding all the time. Another woman, who has seven children under 7 years of age, a husband out of work, herself consumptive [with tuberculosis of the lungs], the baby only 5 weeks old, seemed “rather overwhelmed with it all.” In one home the washing has to hang up in the one living room to dry all day, and in several one basin has to serve for personal washing, the washing of clothes, the mixing of puddings, and the washing-up of utensils. In seven homes out of the 21 there was only the open fire to do all the cooking and heating, in one case for a family of nine, in another for seven, in another for eight, so that baking is quite out of the question (p. 28).

The facilities for cooking in many homes were poor, and recipes had to be adapted to match:

Nine other of our 21 homes have an oven at the side of their open fire, whilst four only are blessed with a close range, and only one home has a gas ring in addition to the ordinary fireplace. One of the distinct points in favour of Miss Petty’s recipes is that they have all been cooked under these disadvantageous circumstances (pp. 28-9).

Energetic efforts needed to be made to make the best of available food. While this was possible, the circumstances of life with large families and few facilities make it impossible for many of the Pudding Lady’s clientele:

For instance, Mrs. D. goes to Bond Street early in the morning and gets quite a good supply of meat pieces for 2d. or 3d. Saturday night late is a good time, or even the Sunday morning auction, when tradesmen from better-class districts will come down to the market streets to get rid of anything they have left over. You can buy beautiful joints of meat at 3d. a pound (p. 29).

Budgeting reflects the demands on and strengths of the women:

Mrs. L. likes to allow 2s. [shillings - now 5 new pence] a day, when things are really going well, to give her family of nine a good breakfast, dinner and tea every day…feeding each person — as she thinks they should be fed …? When times are bad no doubt they have to sink to what so many do: bread and dripping all the week. Mrs. D. says they don’t mind living on tea and bread all the week if they can have a good dinner on Sunday. Several mothers attending the cookery class… satisfy themselves with a couple of hours’ sitting in a good smell. Others seek to find something to cook that “blows out the children and gives them a feeling of having had a huge meal” (pp. 30-1).

The families attempted to encourage their children’s education, reading the bible, hymns and stories aloud to the children and getting older children to read books.

Many of the women had been in domestic service before marriage:

There seems to be a variety of experience as to whether domestic service before marriage is good training for home life or not. On the whole it tends to cleanliness and savoir faire. But Mrs. I. says the cooking she did before marriage was not simple and cheap enough to be of much use to her; Mrs. B. says it was mostly only joints and vegetables where she was in service; Mrs. R. had forgotten most of it by now. On the other hand, a woman not included in these case papers says she “can adapt the dishes she did in service to present requirements.” (p. 31)

There is also information about the role of men in the household:

Miss Petty’s case papers vindicate pretty strongly the place of the father in the home … as a very considerable personal factor in it. From among these 21, only two husbands are bad. … Seven husbands are distinctly good…one knits vests for his baby, and is glad “The Pudding Lady” calls in his dinner hour, because she can show him how to do the shoulders, and knit with four needles instead of two…( p. 32)

There is also information about their financial contribution:

The practice of handing over earnings to the wife varies greatly. Some hand over every penny, and get their pocket-money allowed them just like children. Others keep back so much for clothes, tobacco, and so on…During a wife’s confinement a husband is often exceedingly helpful and domestic. He will cook and clean and manage the children, all, in fact, except handle the new baby.

Children, also, are not quite such trials as one has been led to expect. The baby is always a tyrant… Generally speaking, they do not appear to present much difficulty…On the whole the family life depicted in the case papers is obviously worth every effort to preserve and promote (pp. 32-3).

This colourful case study information is supported by the healthcare professionals’ comments in other articles. For example, an ‘inspector of food and food places’:

Amongst the very poor it is surprising how little food is cooked at home. This may be partly due to lack of energy…, and to the fact that many women have to work for their living, being therefore unable to spare the time and energy for cooking, while at the same time they can buy cooked foods, hot and cold, in almost every district…It seems perfectly clear that the poor cannot get sufficient food, or at any rate the same quantity of nutritious food, as they would if they purchased fresh meat and cooked it themselves (pp. 16-17).

One professional suggests that lack of facilities in homes is the main reason that ‘[t]he poor consume large quantities of fish, both dried and fresh, the majority of which is purchased fried. (p. 17)’. He goes on to explain why:

Quite a number of rooms in tenement dwellings are not provided with an oven attached to the stove, the only means of cooking being a hob grate just large enough to hold one fair-sized saucepan, and too often causing the room to be filled with smoke…The cooking utensils usually consist of a frying pan and a kettle, which are the most important, and of a saucepan. Any food that is left over is kept in a cupboard without any external ventilation, the lower part being usually occupied by coals (p. 18).

Choice of menu was affected by an acceptance that ‘men’ expected at least some meat as part of their diet. The nationally distributed second edition comments on cultural preferences, and you can still see similar comments in cookery books for the least skilled today:

In her work in St. Pancras “The Pudding Lady” was hampered, like so many social workers have been, by the popular prejudice against the use of cheese and the pulses (peas, beans, lentils, and peanuts). This can, however, be overcome by patience and perseverance. Thus at Edinburgh, even before the war, Mrs. Somerville and her fellow Voluntary Health Visitors succeeded in bringing about quite an extensive use of lentils. (p. 75).

The practical is not enough: is it ‘social work’?

In the titles of these publications, and in this quotation, the Pudding Lady work is described as ‘social work’. It contains many elements of family social work as it is understood today. There is a concern for the relationships in the family, care and development of children, thinking about the roles of husband and wife.

But the work is fundamentally practical: helping with cooking and household management. It reflects a concern for family and children’s work in which practical household management is necessary to ensure successful family life. And so it is, but the modern social worker would say ‘the practical is not enough’. There needs also to be a focus also on how relationships and personal growth are nurtured by family life.

There is a recurring critique of social work that its neglect of the practical to focus on the psychological and sociological is a professional aggrandisement. One conservative minister once favoured ‘street-wise grannies’ to social workers; another promoted projects in which motherly non-social workers were sent out to teach mothers how to shop effectively or to play with their children. Such ideas reflect continuing attitudes to women’s roles.

The Pudding Lady documents suggest that this commonplace critique was not appropriate even in the most pressurised of circumstances of the early 20th century. Yet it has always been a popular commentary on the place of women in society that their mothering and family management competence is the main issue to be worked on.

I started these posts on the Pudding Lady with discussion of Mary Ward and her political and social campaigning. Mary Ward wrote the covering encomium of ‘the Pudding Lady’ but is now little remembered, despite her successful novels. It has been suggested recently that this is because her attitude to women’s suffrage was ‘on the wrong side of history’ (Davidson-Smith, 2020). The reason is that, though in many ways supportive of high achievement for women, she opposed the women’s suffrage movements in favour of a ‘forward policy’. She wrote that; ‘Women are not “undeveloped men” but diverse, and the more complex the development of any state, the more diverse. Difference not inferiority… (p. 80.’ Thus women, should take on different roles in society, a more caring, maternal role depending on moral and spiritual strength. She rejected the more boisterous, militaristic and perhaps sordid role of the politics of her time (and is that also true of many times and places?), and wanted to promote women’s strengths and attitudes.

Not surprising, then, that she supported the pudding lady ideal of strengthening women’s roles and skills in family life. It is important to see, in both Miss Petty’s and Mrs Ward’s ideas, their conceptions about the place of women in society. And also not to forget that this is an element, just one element but nevertheless present, of the early thinking of social workers.

And more recently? You might like to comment.

Bibby, [M. E], Colles, [E. G.], Petty, [F.] & Sykes, [Dr] (1910). The pudding lady: A new departure in social work. London: Steads.

Bibby, [M. E], Colles, [E. G.], Petty, [F.] & Sykes, [Dr] (1916). The pudding lady: A new departure in social work (New ed.). London: National Food Reform Association.

Davidson-Smith, D. (2020). On the wrong side of history. History Today, 70(12), pp. 76-83.

Thank you for this insight. Throughout my career I have made reference to earlier publications on social work and residential social work.

The Shorn Lamb by John Stroud

Residential Life with Children by Christopher Beedell

to name but two.

They help ground one in the realities of the damage that structurally imposed poverty does to the dignity of people. They also illustrate that 'do-gooders' have changed nothing as perfectly illustrated by the proliferation of food banks in the 21st Century.

Just listening to the news on the most recent report into the exploitation in the residential child care sector by for profit providers.

I have been writing a book since my retirement with the central thesis that nothing has effectively changed due to the prevailing neoliberal culture of individualism, deserving and undeserving poor still dominating the social work/care landscape. The voices of reason have been effectively sidelined, bought out by shiny things and silenced over the last 40 years that I practiced.